High Performance Web Services with Swift and Protocol Buffers

Every decision connected with the choice of the technology stack is crucial because it has a huge impact on future system limitations which can be hard to predict. Usually, it is a good approach to stick with some battle-tested solutions, especially when we are working on a typical implementation. Everything can become more complicated when we have limited resources or a specific problem to solve.

Swift gives us a lot of modern features that allow us to write safer and more elegant code. There are web frameworks written entirely in Swift that are dynamically evolving and potentially can become a good alternative for widely used frameworks in Java, JavaScript, or Ruby.

Our aim is to test a concept of the full-stack Swift in a real application. In addition, we want to investigate replacing the typically used serialization method of JSON with the more modern Protocol Buffers and see how it affects the performance of web services.

Swift on the server

When Apple made Swift an open-source software at the end of 20151, it became clear that it would open the language to new application areas. The natural consequence was to start the development of new web frameworks in Swift, which would make it possible to implement backend and iOS applications in the same language.

Swift with its strongly typed model and modern features can be a great replacement for the variety of more dynamic languages. Designers of Swift tried to make it safer to write code. Besides the mentioned strong typing, we also get options that simplify operating with nullability, redesigned and safer statements – for example, the switch statement that has to be exhaustive, error handling, and more.

Apple is not alone in showing interest in Swift. IBM seems to invest a lot of resources to integrate Swift with its cloud platform called Bluemix. What is worth mentioning is IBM Swift Sandbox2, which is still in beta but allows us to run Swift code remotely from a web browser. And, last but not least, Kitura3, one of the most dynamically developed Swift frameworks.

At the time of writing this article, there were 4 major web frameworks for Swift: Perfect4, Kitura, Vapor5, and Zewo6. They all can be run on both macOS and Linux and have strong communities behind them. We will focus on Kitura because of its similarity to the Express framework7, great support, and easy configuration.

With Swift on the server, it is now possible to become a full-stack developer without half measures in the form of the hybrid application development nor simply dealing with the JavaScript stack. It gives us more flexibility to choose well-matched solutions. It also gives an opportunity for iOS developers to test themselves on the server-side programming, giving more options to create a feature-oriented, multidisciplinary team.

Moreover, it is now easier for iOS developers to create stubs in case of a temporary lack of server-side development in the early stage of a project.

Protocol Buffers

Usually, when designing communication between a server and an iOS application, we choose JSON as a default serialization method. It has a lot of advantages: readability, flexibility, and good availability of serializers in the majority of most popular web technologies used. In most cases, it is sufficient to use JSON, but when we want to send a lot of data in one shot or our services generate a lot of traffic, it can be reasonable to replace JSON with a more efficient method.

Protocol Buffers8, a method of serializing data developed by Google, has been used internally by the company for about seven years and then publicly published in 2008. It has a lot of advantages compared to JSON, worth mentioning:

- Protocol Buffers comes with the concept of schema. If we want to serialize data in order to send it through the network, we need to define its data type first.

- Every message defined by a schema is strongly typed. In contrast to JSON, every field in the schema has its own data type that cannot be changed. No more unspecified changes of data type between revisions of the API!

- A message can be composed of simple data types or other messages.

- Fields are numbered, which gives backward compatibility to services using the same schema in different revisions.

- Data sent by Protocol Buffers has an apparently smaller footprint.

Protocol Buffers can be used with many web technologies. There are serializers, deserializers, and code generators for the majority of programming languages including Java, C++, C#, Python, Go, Ruby and JavaScript.

Message definitions

To test the concept of the full-stack development in Swift with the use of Protocol Buffers we created the sample server and the iOS application. They communicated via HTTP so they had to have a common proto schema. We started with defining the schema for our sample server. It was a simple web service to serve a list of bank accounts and transactions.

syntax = "proto3";

message Transaction {

uint64 id = 1;

enum TransactionType {

Credit = 0;

Debit = 1;

}

TransactionType transactionType = 2;

string transactionDate = 3;

string bookingDate = 4;

string principalDisposal = 5;

string orderingCustomer = 6;

string beneficiary = 7;

string beneficiaryAccount = 8;

string details = 9;

double amount = 10;

}

message Account {

uint64 id = 1;

string name = 2;

double balance = 3;

double availableFunds = 4;

string iban = 5;

string currency = 6;

string owner = 7;

string ownerAddress = 8;

repeated Transaction transactions = 9;

}

message AccountList {

repeated Account accounts = 1;

}

Every schema definition should start with the version indication. In our example, we used Protocol Buffers in version 3. Next, we defined three message types: Transaction, Account and AccountList.

Fields in the message are strongly typed and numbered. In the Protocol Buffers documentation9 you can find a list of available data types. Most of them are self-explanatory: double, float, string, int32, int64, uint64, etc. The numeric tag should be unique within the type definition and is placed after the field name and the equality sign.

Defining enums is similar to defining messages, the only difference is that we don’t place a type before a name. Complex data types can be defined inline, just before the use. In our example we defined TransactionType as an enum with two possible values: Credit and Debit so we can distinguish between incomes and outcomes in the transaction list.

Arrays can be defined by the repeated keyword which should be placed before a type of element in the field definition. In our example, we defined transactions as a repeated Transaction type.

To transform our definitions to the form that could be used by serializers and to generate the managing code we need to install protoc compiler. To use them inside a Swift application we need also the Swift Protobuf library.

First, we install the compiler via Homebrew10:

brew install protobuf-swift

Now we can build the Swift Protobuf library. We use the 0.9.903 version so we check out the 0.9.903 tag:

git clone https://github.com/apple/swift-protobuf.git

cd swift-protobuf

git checkout tags/0.9.903

swift build -c release -Xswiftc -static-stdlib

This will create a binary that should be available in the system PATH. We can add its path to ~/.bash_profile file using the export statement or simply copy it to /usr/local/bin:

sudo cp .build/release/protoc-gen-swift /usr/local/bin/

Assuming we keep the message definitions in DataModel.proto, we can generate Swift classes to the Source directory by the following command:

protoc --swift_out=Sources/ DataModel.proto

And that’s it! We are free to use our model in web and mobile applications.

Let’s write some code

We started with the server implementation. To simplify the process of creating the project structure, we used Swift Package Manager:

mkdir protobuf-server

cd protobuf-server

swift package init --type executable

To add the required dependencies we edited the Package.swift file:

// swift-tools-version:3.1

import PackageDescription

let package = Package(

name: "protobuf-server",

dependencies: [

.Package(url: "https://github.com/IBM-Swift/Kitura.git", majorVersion: 1, minor: 7),

.Package(url: "https://github.com/IBM-Swift/HeliumLogger.git", majorVersion: 1, minor: 7),

.Package(url: "https://github.com/apple/swift-protobuf.git", Version(0,9,903))

]

)

It is important to use the same Protocol Buffers version in the project as used to generate our models, so we chose the 0.9.903 version here as well.

We can write the server code in any favorite editor, but if our favorite editor is Xcode, then we can also create Xcode project to be able to run our server from the IDE.

swift package update

swift package generate-xcodeproj

open protobuf-server.xcodeproj

We wanted our server application to load account and transaction information once on the boot to minimize latency not related to serialization and networking. We used Ruby and some handy library called faker to generate fake financial data. The script generates CSV documents to be easily loaded into the web application.

require 'csv'

require 'faker'

def random_account(id, name)

account_name = name

balance = 12999.56

available_funds = 9876.12

iban = Faker::Bank.iban

currency = 'EUR'

owner = Faker::Name.name

owner_address = Faker::Address.street_address + ', ' + Faker::Address.city + ' ' + Faker::Address.zip + ', ' + Faker::Address.country

[id, account_name, balance, available_funds, iban, currency, owner, owner_address]

end

def random_transaction(id, date_offset)

now = Date.today

transaction_type = rand(0..1)

transaction_date = now - date_offset

booking_date = Faker::Date.between(transaction_date, transaction_date + 3)

principal_disposal = Faker::Name.name

ordering_customer = Faker::Name.name

beneficiary = Faker::Name.name

beneficiary_account = Faker::Bank.iban

details = Faker::Lorem.sentence

amount = Faker::Commerce.price

[id, transaction_type, transaction_date, booking_date, principal_disposal, ordering_customer, beneficiary, beneficiary_account, details, amount]

end

CSV.open('Mocks/accounts.csv', 'w', col_sep: ';') do |csv|

csv << random_account(1, 'Main account')

csv << random_account(2, 'Second account')

end

date_offset = 0

CSV.open('Mocks/transactions_1.csv', 'w', col_sep: ';') do |csv|

(0..1000).each do |i|

offset = 1000000

csv << random_transaction(offset - i, date_offset)

if i % 20 == 0

date_offset += 1

end

end

end

date_offset = 0

CSV.open('Mocks/transactions_2.csv', 'w', col_sep: ';') do |csv|

(0..10000).each do |i|

offset = 2000000

csv << random_transaction(offset - i, date_offset)

if i % 20 == 0

date_offset += 1

end

end

end

We wanted our stub service to serve a list of two accounts with a different number of transactions to see how the response times depend on the payload size. So we generated two collections of transactions with 1000 and 10000 transactions respectively.

The data loading process is realized by DataLoadHelper class, and it simply reads the corresponding CSV files and returns them as Swift objects. See the sampling method which loads the transaction list below.

private func loadTransactions(id: UInt64) -> [Transaction] {

let filename = "transactions_" + String(id)

do {

let transactionRows: [String] = try loadStringFromFile(filename: filename).components(separatedBy: .newlines)

return transactionRows.flatMap { row in

if row == "" {

return nil

}

let fields = row.components(separatedBy: ";")

return Transaction(fields: fields)

}

} catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

return []

}

}

private func loadStringFromFile(filename: String) throws -> String {

guard let path = bundle?.path(forResource: filename, ofType: "csv") else {

throw DataLoadHelperError.fileNotFound

}

do {

return try String(contentsOfFile: path)

} catch {

throw DataLoadHelperError.fileNotLoaded

}

}

Unfortunately, at present there is no option to copy assets to the main Bundle from the Swift Package Manager level so we created a separate bundle just for the generated CSV files:

private lazy var bundle: Bundle? = {

let url = URL(fileURLWithPath: #file).deletingLastPathComponent().deletingLastPathComponent()

return Bundle(path: url.appendingPathComponent("MocksGenerator/Mocks").path)

}()

For better comparison with JSON serialization, the Accept header was used. Thanks to that we can control the format in which we want data to be serialized from the iOS application level.

To manage this feature we created HttpHeaderHelper that can check the headers and set the desired content type. If a user of our API won’t set Accept headers, we want the JSON serialization to be used as a more common one.

import Foundation

import Kitura

enum AcceptHeader {

case json

case protobuf

var contentType: String {

switch self {

case .json:

return "application/json"

case .protobuf:

return "application/octet-stream"

}

}

}

final class HttpHeadersHelper {

func acceptHeader(headers: Headers) -> AcceptHeader {

let accept = headers["Accept"] ?? "application/json"

switch accept {

case "application/json":

return .json

case "application/octet-stream", "application/x-protobuf", "application/x-google-protobuf":

return .protobuf

default:

return .json

}

}

}

The starting point for every Kitura server is simply the main.swift file. It is a place where we can initialize the Router object, prepare our stub objects, add an HTTP server to the Router and start Kitura’s runloop.

import Kitura

import HeliumLogger

import SwiftProtobuf

// Initialize HeliumLogger

HeliumLogger.use()

// Load data from CSV files

let dataLoader = DataLoadHelper()

let accountList = dataLoader.loadAccountList()

let accountDictionary = dataLoader.mapAccounts(accountList: accountList)

// Http Headers Helper to recongnize supported Accept values

let httpHeadersHelper = HttpHeadersHelper()

// Create a new router

let router = RouterCreator.create(accountList: accountList, accountDictionary: accountDictionary, httpHeadersHelper: httpHeadersHelper)

// Add an HTTP server and connect it to the router

Kitura.addHTTPServer(onPort: 8080, with: router)

// Start the Kitura runloop (this call never returns)

Kitura.run()

As you may notice, we create the router object by our custom object RouterCreator and run our server on port 8080.

Kitura’s router is responsible for defining our endpoint’s routes. Besides the /accountList endpoint that responds with the list of all accounts we also created one endpoint that allows us to pick one account with a transaction list. It is available for the route of “/account/:accountId” where accountId should be a UInt64 number.

let router = Router()

// Handle HTTP GET requests to /accountList

router.get("/accountList") { request, response, next in

let acceptHeader = httpHeadersHelper.acceptHeader(headers: request.headers)

response.headers.append("Content-Type", value: acceptHeader.contentType)

switch acceptHeader {

case .json:

let accountListJSON = try accountList.jsonUTF8Data()

response.send(data: accountListJSON)

case .protobuf:

let data = try accountList.serializedData()

response.send(data: data)

}

next()

}

// Handle HTTP GET requests to /account/:accountId

router.get("/account/:accountId") { request, response, next in

guard let accountId = UInt64(request.parameters["accountId"]!),

let account = accountDictionary[accountId] else {

response.send("{\"error\" : \"Invalid id provided.\"}");

next()

return

}

let acceptHeader = httpHeadersHelper.acceptHeader(headers: request.headers)

response.headers.append("Content-Type", value: acceptHeader.contentType)

switch acceptHeader {

case .json:

let accountJSON = try account.jsonUTF8Data()

response.send(data: accountJSON)

case .protobuf:

let data = try account.serializedData()

response.send(data: data)

}

next()

}

All classes generated by Protocol Buffers are of the type SwiftProtobuf.Message which has a bunch of serialization and deserialization methods. To get data serialized to Protocol Buffers we just call serializedData() method on an object, and to serialize an object to JSON we can use jsonUTF8Data() method.

If we created an Xcode project for the application and want to run it directly from IDE, we can do that by using a standard ⌘ + R (Command + R) shortcut. It is important to choose our executable schema because it is not selected automatically. If everything is fine, it should look like in Fig 1.

.webp)

If you don’t want to generate an Xcode project then you can build and run the server from Terminal:

swift build

.build/debug/protobuf-server

Now we can open a browser and go to http://localhost:8080 address to see Kitura’s placeholder page.

The article includes only fragments of the original solution. The full source code of the server application is available on Github11.

iOS application

The source code of the iOS application is also available on Github11. We decided to use the Alamofire library to simplify the networking layer and use some built-in diagnostic features. To manage dependencies we used Cocoapods.

use_frameworks!

target 'ProtobufSampleApp' do

pod 'Alamofire', '~> 4.4'

pod 'SwiftProtobuf', '0.9.903'

end

post_install do |installer|

installer.pods_project.targets.each do |target|

target.build_configurations.each do |config|

config.build_settings['SWIFT_VERSION'] = '3.0'

end

end

end

We had to use the same Swift Protobuf version as in the code generation step and the server application. Otherwise, the generated code would not correspond to the Protocol Buffers version used in the application.

The process of data deserialization on the client-side is also easily manageable. We simply get the data from the responseData property and pass it to the corresponding SwiftProtobuf.Message object.

func getAccountList(acceptHeader: AcceptHeader, completion: @escaping (Bool, AccountList?, DurationTimes?) -> Void) {

Alamofire.request(host + "/accountList", method: .get, parameters: nil, encoding: URLEncoding.httpBody, headers: acceptHeader.generate())

.validate()

.responseData { response in

guard let data = response.data else {

completion(false, nil, nil)

return

}

do {

var accountList: AccountList!

switch acceptHeader {

case .protobuf:

accountList = try AccountList(serializedData: data)

case .json:

accountList = try AccountList(jsonUTF8Data: data)

}

let durationTimes = DurationTimes(totalDuration: response.timeline.totalDuration, requestDuration: response.timeline.requestDuration)

completion(true, accountList, durationTimes)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

We also wanted to know how long it takes for the server to respond, so we also got request duration times. The totalDuration is the time interval in seconds from the time the request started to the time response serialization completed. The requestDuration is the time interval in seconds from the time the request started to the time the request completed.

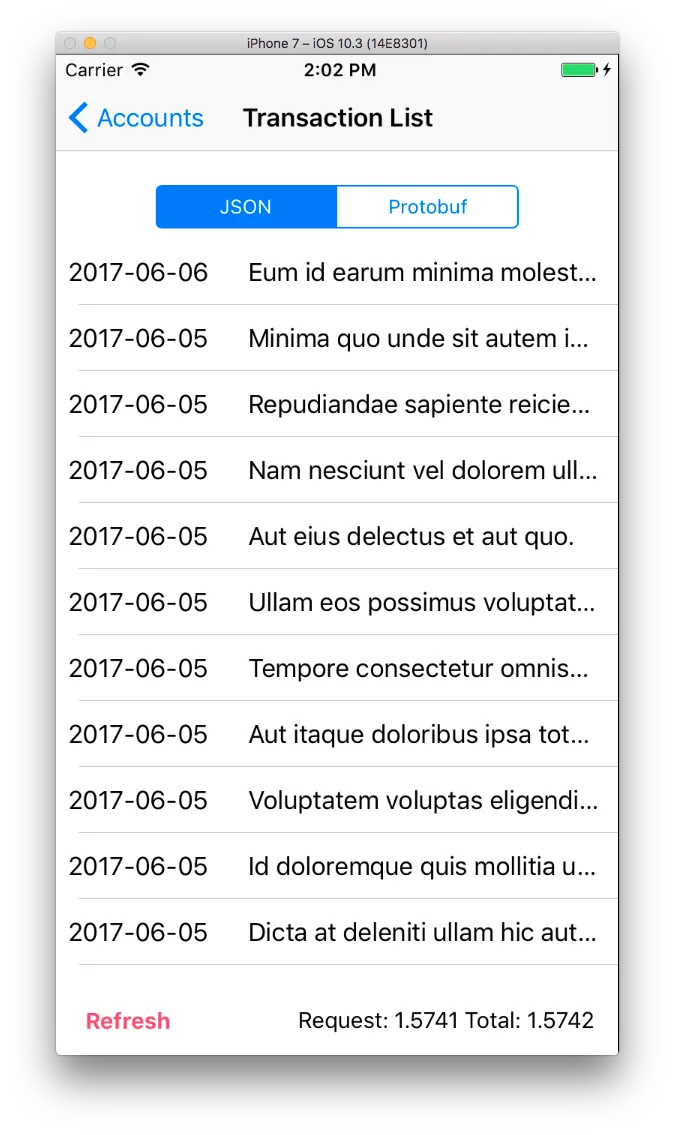

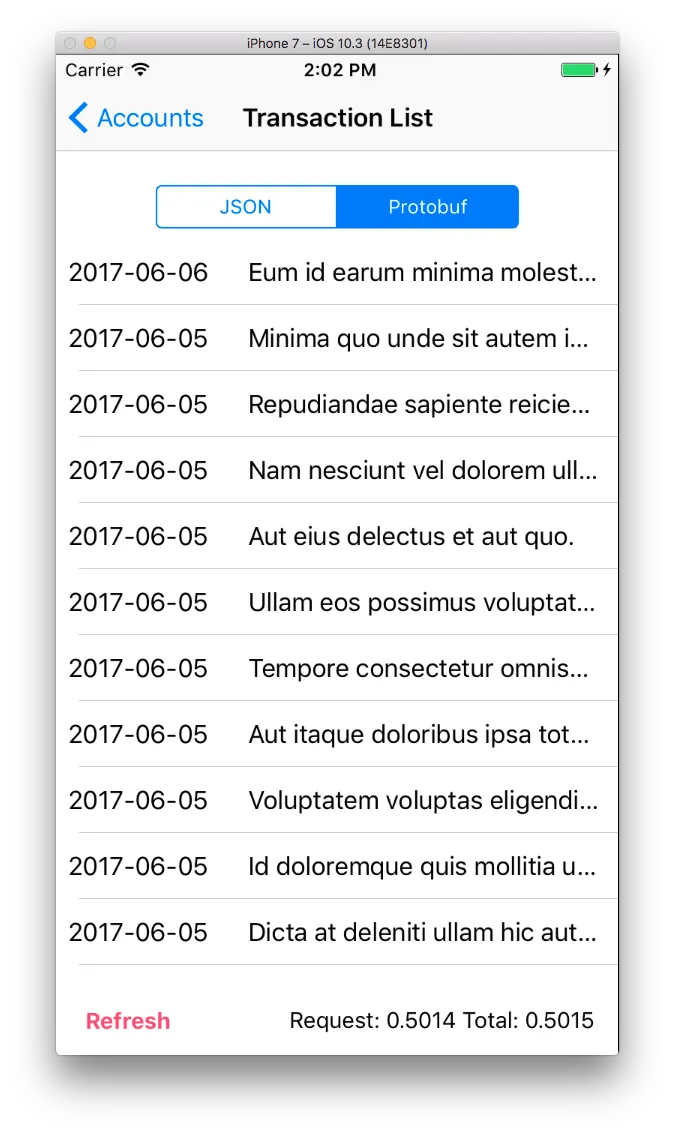

Fig 3 and Fig 4 include screenshots of the sample application where the communication was JSON and Protocol Buffers serialized respectively.

As you may notice, request and total duration times for Protobuf are significantly shorter than using JSON serialization (about 3 times). We run the app in the same environment 20 times to get the average duration times for one client.

| Lp | Request duration times for Protobuf | Request duration times for JSON |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.6115 | 1.7675 |

| 2 | 0.5724 | 1.9296 |

| 3 | 0.5623 | 1.7717 |

| 4 | 0.5584 | 1.7954 |

| 5 | 0.5693 | 1.7769 |

| 6 | 0.5657 | 1.7222 |

| 7 | 0.5605 | 1.8475 |

| 8 | 0.5681 | 1.7225 |

| 9 | 0.5647 | 1.7475 |

| 10 | 0.5625 | 1.8198 |

| 11 | 0.5602 | 1.7694 |

| 12 | 0.5627 | 1.6906 |

| 13 | 0.5585 | 1.8076 |

| 14 | 0.5599 | 1.7052 |

| 15 | 0.5896 | 1.6936 |

| 16 | 0.5663 | 1.7563 |

| 17 | 0.5594 | 1.7363 |

| 18 | 0.5622 | 1.7105 |

| 19 | 0.5573 | 1.6998 |

| 20 | 0.5639 | 1.8634 |

It gives us the average values of 0.56677 seconds for Protobuf and 1.766665 seconds for JSON. The table below contains the summary of payload sizes of our test requests.

| Request | JSON | Protocol Buffers |

|---|---|---|

| account/1 | 317KB | 162KB |

| account/2 | 3.1MB | 1.6MB |

| accountList | 3.4MB | 1.8MB |

For the sample data, the payloads for Protocol Buffers are two times smaller than JSON’s in every case. Such a kind of saving is especially important for mobile devices where the web services should respond quickly.

Load tests

We also wanted to test our sample server in more extreme conditions to look at how it would behave for 20, 50, 100, 200, and 300 users using our API in the local environment simultaneously. We chose to use Gatling12 framework as it is very easy to record and run load tests locally.

Gatling is available as a zip archive containing binaries and dependencies, so it is ready to use just after download. The bin directory contains two executable scripts: gatling.sh and recorder.sh. Gatling Recorder is a handy tool for recording simulators in a form of Scala13 script.

.webp)

The recorder works as a local proxy that saves all requests going through it. After clicking on the ‘Start’ button, the recorder listens on a port defined in the ‘Listening port’ field. Gatling scripts are saved in the output folder after recording. We chose to configure the Firefox browser to use Gatling Recorder, so we went to the Preferences, Advanced, Network tab, and clicked on ‘Settings…’ button in the Connection section. We wanted to configure proxy manually and chose the Gatling Recorder’s port of 8000, as in Fig 6.

.webp)

After configuring the browser to use Gatling’s proxy, and starting the recorder, we used our API via Firefox browser to cover all our endpoints in a single session:

- localhost:8080/account/1

- localhost:8080/account/2

- localhost:8080/accountList

To prepare the Protobuf scenario, we repeated the procedure from starting a new session in Gatling Recorder. We used the ModifyHeaders plugin to modify Accept header, as in Fig 7.

Having two simulations in the output folder allows us to create a Gatling project and adapt them to cover our cases of using the API simultaneously by more than one user. To do that, we used SBT14 and IntelliJ IDEA15. SBT is a build tool for Scala that simplifies all processes required for building Scala projects including dependency management, testing, and deployment.

SBT and Scala are available as an IntelliJ plugin. After creating SBT project, we added the required dependencies in the build.sbt file:

enablePlugins(GatlingPlugin)

scalaVersion := "2.11.8"

scalacOptions := Seq(

"-encoding", "UTF-8", "-target:jvm-1.8", "-deprecation",

"-feature", "-unchecked", "-language:implicitConversions", "-language:postfixOps")

libraryDependencies += "io.gatling.highcharts" % "gatling-charts-highcharts" % "2.2.5" % "test,it"

libraryDependencies += "io.gatling" % "gatling-test-framework" % "2.2.5" % "test,it"

In the project/plugins.sbt file we also added Gatling Plugin to be available in the build process:

addSbtPlugin("io.gatling" % "gatling-sbt" % "2.2.1")

addSbtPlugin("com.typesafe.sbteclipse" % "sbteclipse-plugin" % "3.0.0")

The simulations generated by Gatling Recorder had to be placed inside scr/test/scala, and are as follows:

import io.gatling.core.Predef._

import io.gatling.http.Predef._

class TransactionsJSONSimulation extends Simulation {

val httpProtocol = http

.baseURL("http://localhost:8080")

.inferHtmlResources()

.acceptHeader("text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8")

.acceptEncodingHeader("gzip, deflate")

.acceptLanguageHeader("en-US,en;q=0.5")

.userAgentHeader("Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.12; rv:53.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/53.0")

val headers_0 = Map("Upgrade-Insecure-Requests" -> "1")

val scn = scenario("TransactionsJSONSimulation")

.exec(http("account_1_json")

.get("/account/1")

.headers(headers_0))

.pause(8)

.exec(http("account_2_json")

.get("/account/2")

.headers(headers_0))

.pause(27)

.exec(http("accountList_json")

.get("/accountList")

.headers(headers_0))

setUp(scn.inject(atOnceUsers(100))).protocols(httpProtocol)

}

TransactionsProtobufSimulator is analogical, but has a different acceptHeader. By increasing and decreasing the atOnceUsers method parameter we can change the number of users using our API at the same time during the simulation. The source code of the whole Gatling project is available on GitHub11.

To run the simulation we open the terminal and run the sbt from the project level:

sbt

Then we run the test target:

gatling:test

Gatling’s reports are generated into the target/gatling folder and are in the HTML format as in Fig 8 and Fig 9.

As you may notice, Protocol Buffers endpoints have shorter duration times, and in the case of 100 users using the API simultaneously, we got a timeout for JSON serialization for 66 requests. Reports also include the duration of the whole simulation, number of successful and unsuccessful requests, number of requests per second, response times for various different percentiles.

They also include charts for the number of active users along with the simulation, response time distribution, response time percentiles over time, number of requests per second, and number of responses per second. The summary of the simulations is shown in the tables below.

| JSON | 20 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KO % | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.220 | 0.440 | 0.550 |

| Req/s | 1.071 | 1.667 | 1.852 | 3.727 | 5.590 |

| Min response time (ms) | 440.000 | 539.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Max response time (ms) | 13899.0 | 33567.0 | 59644.0 | 59890.0 | 59558.0 |

| Mean of response time (ms) | 4492.00 | 11663.00 | 19400.00 | 12170.00 | 9180.00 |

| Standard deviation | 3724.00 | 8917.000 | 20716.00 | 17373.00 | 14680.0 |

| JSON | 20 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protobuf | 20 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| KO % | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.280 |

| Req/s | 3.00 | 4.839 | 3.947 | 5.825 | 6.383 |

| Min response time (ms) | 178.00 | 145.000 | 134.00 | 107.000 | 0.000 |

| Max response time (ms) | 3917.0 | 10231.00 | 30182.0 | 44839.00 | 59945.00 |

| Mean of response time (ms) | 1426.0 | 3557.00 | 14955.0 | 21363.00 | 15919.00 |

| Standard deviation | 1017.0 | 2562.00 | 11704.0 | 16881.00 | 20545.00 |

The JSON endpoints needed more time to respond and failed earlier. The Protocol Buffers endpoints could handle more requests per second. They also had significantly smaller minimal and mean response times. More interestingly, the minimum response time before timeouts decreased from 178 to 107 ms, and maximum response times increased less dynamically.

Conclusions

Open Source Swift created a great opportunity for the development of new frameworks for web applications. We observe a stable growth of these solutions and hope they will be more commonly used in the nearest future.

Protocol Buffers is a good alternative for JSON-based web services. Because of its schema approach, it allows us to design safer web services with less effort than using JSON serialization. Smaller payloads also increase the number of requests per second that can be handle by the server.

We created a working solution in Kitura framework using the serialization of JSON and Protocol Buffers and a basic mechanism that allows us to switch serializers from the iOS application side.

Despite the fact that Swift frameworks are still in dynamic development, and the language itself is also not free from significant changes, it can be considered as a good alternative for the battle-tested technologies in case of working on experimental solutions.

This article was originally published on Codete Blog, but the blog was shut down in mid 2024. The original URL: High performance web services with Swift and Protocol Buffers.

References

-

“Swift is Open Source”, Apple Developer (3 December 2015). https://developer.apple.com/swift/blog/?id=34 ↩

-

IBM Swift Sandbox: https://swift.sandbox.bluemix.net/#/repl ↩

-

Kitura: http://www.kitura.io ↩

-

Perfect: http://perfect.org ↩

-

Vapor: http://vapor.codes ↩

-

Zewo: http://zewo.io ↩

-

Express: https://expressjs.com ↩

-

Protocol Buffers: https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers ↩

-

Protocol Buffers Documentation: https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/proto ↩

-

Homebrew: https://brew.sh ↩

-

Protobuf Samples: https://github.com/codete/protobuf-samples ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Gatling: http://gatling.io ↩

-

Scala: https://www.scala-lang.org ↩

-

IntelliJ IDEA https://www.jetbrains.com/idea/download ↩

Michał Cichoń is a software engineer based in Kraków, Poland.

With over 15 years of experience in web and mobile development, he specializes in building iPhone and iPad applications using Swift and Objective-C.

He currently works on a social media app developed by a small, data-driven team, where experiments and A/B testing shape user experience. Over the years, he has collaborated with financial institutions, biomedical companies, and startups from New York, Berlin, and beyond.